ZAMBIA LETTERS, 13

- Ludvig Uhlbors

- 22 juni 2025

- 5 min läsning

Uppdaterat: 28 juni 2025

15/06/2025

We take an early morning in order to be at the Livingstone museum when they open. Mr. Mwata Chibweka meets us at the entrance. He is older than both me and Hanna and misses two front teeth in his upper jaw, a characteristic of some Zambian tribesmen. In connection with their initiation rites, they sometimes pull those teeth out, a very painful process.

There is nothing academic or intellectualized about him, even though he has education. He keeps his voice low and his gaze is intense, carried by a focused presence. I´ve found the same energy in other people who also have spent a lot of time in the wilderness.

When we ask Mr. Chibweka to tell us about the Makishi tradition, he begins by talking about nature and the relationship to the animals and plants that live in the landscape.

”The religion (Christianity) say that this is which craft. It is not. We teach them (the children) to be responsible. We show them what to eat and how much and how to care for the elderly. This knowledge has been with all the peoples but it has been lost. So people from other tribes send their children to us. It is the children who wants to come. Some say we take children from their parents but it isn’t true.”

”Every child learns this: conserve nature, do not kill birds. Animals are important to us. We don´t teach them to kill, but to take care for the river so that for generations to come, it will be there.”

”We teach them at an early age, 7-12 years, not when they have grown up. We do it (the circumcision) in may or June, when they heal well.”

”We were taught by our parents and it is our duty to teach our children so that nature remains intact. On this side the forest is finished (he points to the north), which means that our tradition will end. But if we can preserve our nature, near the people, then we can teach.”

”There are four tribes in the North western region who uphold our traditions. The Luvale, the Mbunda, the Chokwe and the Luchazi.”

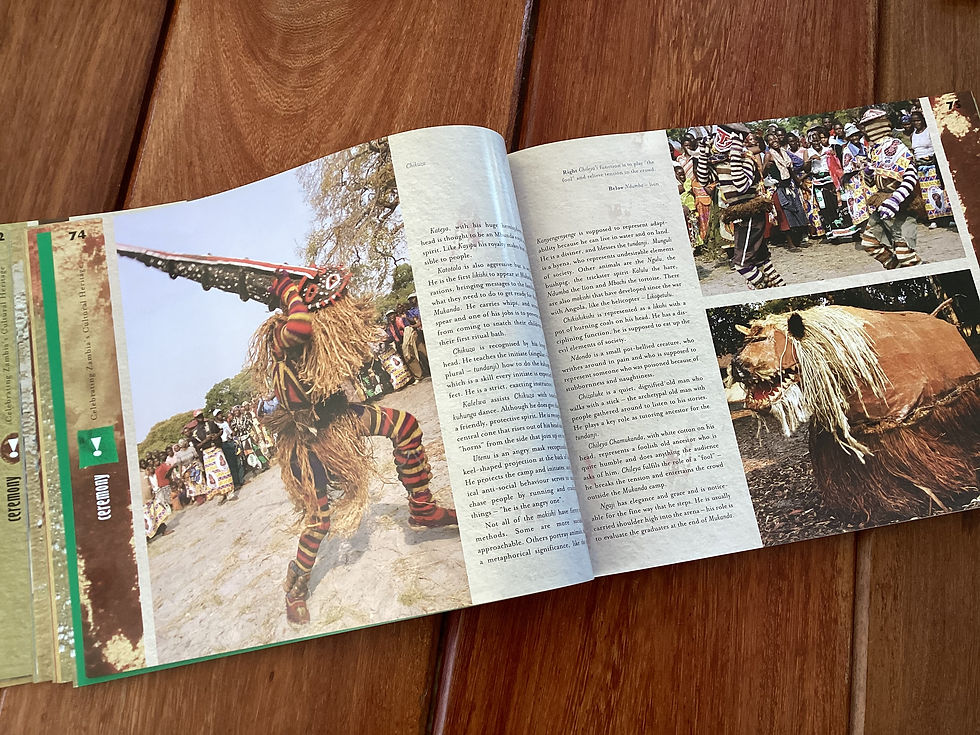

He takes us into the exhibition and shows us the masks and photographs that are on display. He tells us that there are 200 types of masks. In one of the pictures, the mask wearers have a headdress that is shaped like a bowl with a rim running across it. It is called the Chileta Moture (this may be spelled wrong, I apologize) and it is a hat that the initiates are supposed to wear. They wear it when they return home from the camp. The hat is painted in the traditional colors of red, black and white. On that occasion, they also wear a form of skirt that is made of straw. Mr. Chibweka calls it Sombo (dito). They also have a stick with a small ball attached to it. It makes a rattling sound because it is filled with beans. The same balls are also attached to their ankles.

When the boy comes home, wearing this costume, the mother must identify her child and inspect him to make sure he is not injured. The ritual begins with her putting money on the hat and saying “open now”. He then takes his costume off. If it is the right child, she exclaims “oooooh…” Then she will examine him, from head to toe. She checks everything on his body. Fingernails, toes, lips and armpits.

During the camp, each child is taken care of by a person called Chilombola. He is the one who gives the child the traditional medicines that make the boy heal after the circumcision. He is also responsible for the boy’s health during the rest of the ritual. If the mother recognizes her child and finds no injuries on him, she gets to keep the money she has put on top of the hat. The Chilombola’s responsibility for the boy lasts for the entire six months that the camp (Mukunda) is running.

Mr Chimbweka says that an important part of his spirituality is knowing that the knowledge he has received from his ancestors is passed on to his children. If there are no forests near human habitations, he and his tribe cannot live up to that commitment.

He gives several examples of such knowledge during our conversation, for example when he tells us how the Luvale people use bark from trees that is treated with mortar until it becomes soft. They do not use wool in their villages, only this material, which can serve as both a blanket and as details in the ”Chalet moture” that the boys wear when they return to their mother. The mashed bark is dyed black by soaking it in the river for a long period. In the same way, they produce white paint by exposing ash to the river. This is then used as a pigment. There are also other methods of producing these colors (red, black and white are the main colors, they are symbolic and used to paint the Makishi masks in patterns.)

”The creation of pigments connect to the Makishitradition and to the masks. For example ”Chindora Ngunda" is a white mask used to remember when the white people came to Angola, which is also where our tribes came from wsoriginally. ”Ti-Mukunda” is a brown dye used to paint other masks. We acquire black from certain leaves: ”Tegualamome”. The leaves will soak in the river over night after having boiled for ten minutes. This absorbs back soil from the river. White is being extracted from a flower, ”Saiso”. It is found within the green parts of the plant. In our tribe the plant is called ”Niembe”. Brown can be taken from the bark of the Rose tree.”

He goes on to name the different parts of the costume:

”Massada is the name of the skirt in cloth which is used by the masks. The name of the item which is tied to the hip is Chuwamba. The balls connected to the stick, and the feet, are called Sango.”

He says that the mask wearers hide their masks in order to be able to use them again. Nobody else knows where they are hidden. These masks are given to the boys during the camp, but the initiates are also shown how to make new ones. The person who owns the camp and organizes it is called Chithizika. He will distribute these mask to the right boys, when he sees who is able to handle them. A person who knows how to handle a mask well can receive money when they perform. There are according to Mr Chimbweka 200 different masks.

One such mask is Mwanapwevo, a female deity. She cultivates the land. If you work it the way she teaches, she will come alive. She teaches people not to grieve for their loses, but to work and sing.

”The first thing they learn in the Mukunda is: this is tree. This is pig.”

”The Gods gave these things to us to use wisely. If we destroy them we have nothing.”

”The secrecy of the Mukunda is connected to the identity that the ritual gives. Anyone can learn this, if you are a man. So it is not exclusive, the secrecy is a result of the teaching. The teaching only happens in these camps. That is why it becomes secretive. We teach the way of life, which is connected to this knowledge.”

Part of the secrecy surrounding this tradition is the hallowing of the Mukunda space. The Chithizika will erect two wooden poles at the entrance to the Mukunda. These are taken from dead or fallen trees, as everything else used in the camp. The poles are called Monongo. They signal the entrance to the hallowed space, a point which no outsider might cross. Mothers and relatives who approach these camps to give food to their children will leave it hanging on these Monongo poles.”

Kommentarer